How Magical Realism Reflects the Queer Experience

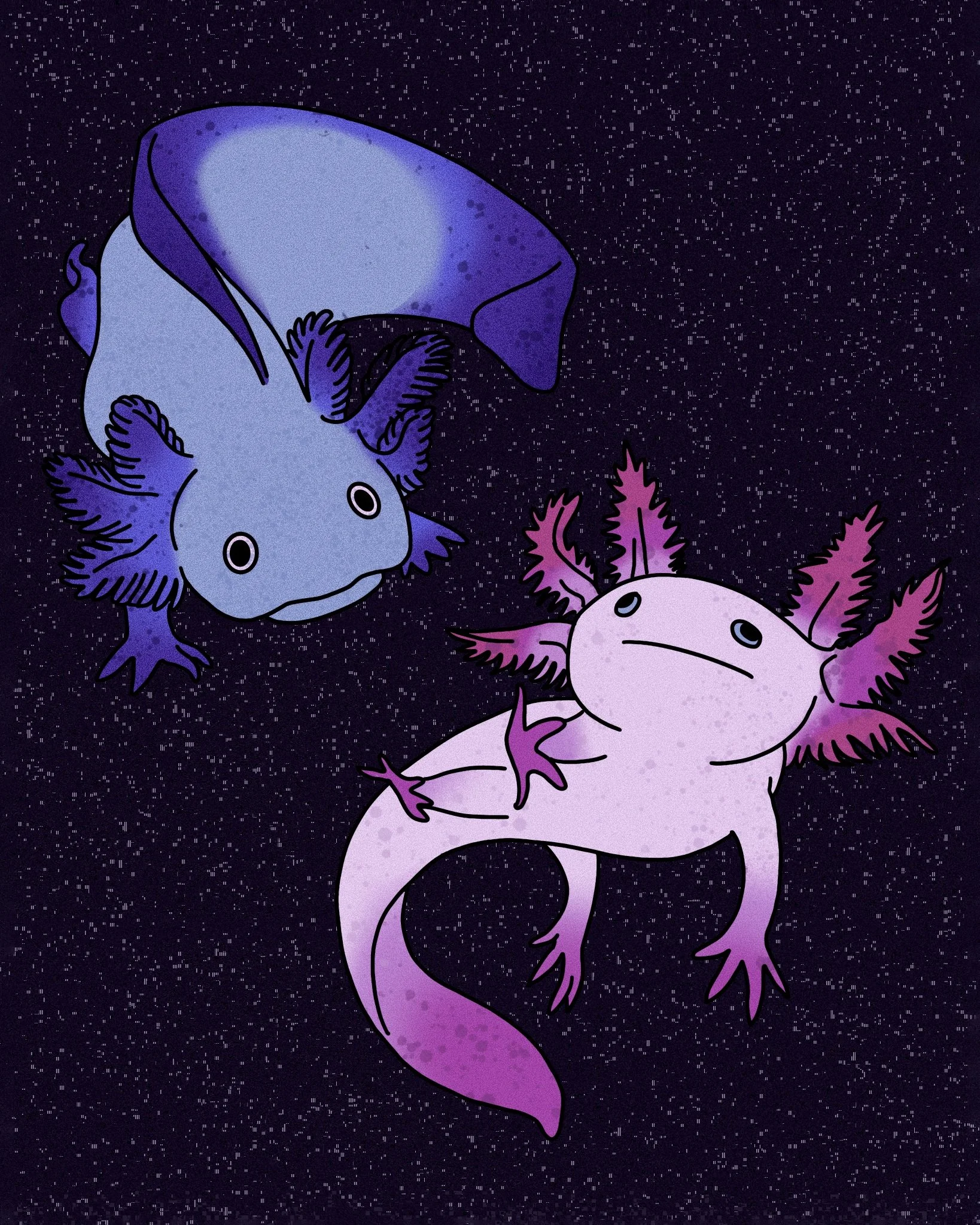

Illustration by Malaika Astorga

As we continue to get sucked into sanitized versions of LGBTQ+ identities, one thing is becoming clear: I’m tired of mainstream queer media. The same sentiment could be expressed more succinctly with the words “I’m tired of mainstream media”, but it’s the queer ones that are a particular thorn in my side. The increasing sanitization of queer stories may make them more digestible for cishet audiences, but it inevitably comes at the cost of reducing the queer experience to what can be easily turned into Funko Pops and brand deals.

In the search for a more authentic experience, I—surprisingly enough—turned to a genre that isn’t necessarily known for its queer representation: magical realism. For someone with surface-level knowledge of magical realism, it might be more fitting to discuss the literary genre in its initial context: originating from Latin America in a period of significant political turmoil and using unimaginative language when describing imaginative events to convey messages of social and political critique. However, a closer look at traits unifying the works of the genre reveals parallels between the magical realist experience and the queer experience.

Magical realism employs a technique called authorial reticence, or the intentional withholding of information about the world from the audience. Authorial reticence, and the effect it has on the reader, wonderfully reflect the lack of preparedness to navigate a cishet world as a queer person. After all, don’t you—the queer person reading this—ever feel like your peers were given some kind of survival guide that got mysteriously lost in the mail in your case? Like you missed a life-altering memo?

Another point of comparison is that the underlying political aspect of magical realist works serves as a mirror for the inherently political lives of queer people. In a world where queer bodies and relationships are constantly exploited as discussion points in TV debates or potential vote-sways to garner a few votes in elections, the removal of political undertones from media can feel like a flattening of queer storylines. Even though magical realist works rarely discuss queer issues, the fundamental connection between a narrative and its underlying sociopolitical contexts offers comfort for those who feel that their lives, too, have an underlying context.

Perhaps most importantly, magical realism turns its eye on the reader; it is the relationship between the text and the audience that adds an extra layer of depth to magical realist works. Everyday life often marginalizes queer experiences and people, whether they’re characters in the story of life or an audience for cishet realities. Conversely, crafting a magical realist narrative requires thinking not only about the in-text world but also the world of those reading it: how much should the reader know about the character? How is the reader supposed to distinguish between what’s real and what’s fake – and within this world, is there even a meaningful difference?

Julio Cortazar’s “Axolotl” is a story with a relatively simple premise – it’s about a man who turns into an axolotl. The story is a classic example of a magical realist text: the real-world setting of Paris is contrasted with the fantastical events, and the reader never really finds out how the transformation happens (in the original context, the story was meant as an extended metaphor for the political situation in Argentina).

“Axolotl” brings special attention to the process of transformation in a way that may be comforting for transgender audiences, even though there is no mention of gender in the story itself. The narrator’s recount of his transformation is parallel to the process of exploring one’s gender identity: the initial fascination (“I stayed watching them for an hour and left, unable to think of anything else”); the intrinsic feeling of connection with the unknown (“They and I knew.”); the feeling of removal from one’s old self (at the end of the story, now in the aquarium alongside the axolotls, the narrator starts to refer to his human version, which still visits, in third person) and that the transition was meant to happen all along. The narrator fully embraces being an axolotl, with all of its weirdness and with full awareness that it means at least partially breaking away from what it means to be a “regular” person. Ain’t that the representation you sometimes need in place of pretty protagonists on both big and small screens, desperately attempting to convince cishet audiences that “queer people are just like you, really”?

In contrast to “Axolotl”, Chavissa Woods’ short story collection Things to Do When You’re Goth in the Country focuses more on the queer than the magical realist. Although some stories in the collection are just plain and simple literary fiction, the story which leans into magical realism the most is “A New Mohawk”, a story of a young trans man who (how very topically) one day wakes up with the Gaza Strip attached to his head. “Take the Way Home that Leads Back to Sullivan Street” is a story of a lesbian and her partner who share hallucinations (or are they hallucinations?) after doing drugs at their in-laws’ Mensa party. Almost every story in the collection features queer characters, and none of them stray away from portraying the characters as disgustingly human, with all the ugliness it requires.

Woods seems to get something that many contemporary creators of queer storylines don’t get: that delving into the peculiarities of the queer experience isn’t a bad thing, and that creating art that fits cishet ideals of “normality” shouldn’t be the goal. I think the most vivid element of TTDWYGITC is its inability to be sterilized and turned into Shein merchandise: it’s queerness you cannot get out with bleach and capital.

If you’re a queer reader, fatigued with the increasingly boring and sterilized portrayals of queer realities in media, go to a library and grab a book from the “magical realism” shelf. After all, the original rainbow flag included a stripe symbolizing magic.

Magdalena Styś is a jack of all trades and a master of putting them all into their schedule. You can check out their work here or follow them on Instagram.

Malaika Astorga is the Co-Founder & Creative Director of Also Cool. She is a Mexican-Canadian visual artist, writer, and social media strategist currently based in Montreal.